May 15, 2019: Desire and Aversion

The first time I thought of writing this I was just getting into the shower. Looking forward to the feeling of the nice, warm water, I slammed the shower dial to full heat. Of course, the water was ice cold at first and I immediately recoiled--mentally more than physically (my dorm room shower wasn't spacious enough to perform such a maneuver). It made me think of something my dad had said: people have gotten so used to modern comforts nowadays and don't have to endure nearly as much physical discomfort as they once did. More broadly, I thought about how desire and aversion are such massive components of our lives and decisions and about how automatic they are.

We are constantly confronted by desire and aversion. I might long for something sweet after dinner and satisfy this desire by gorging myself on it. Then, I dislike the feeling of my stomach getting too full and stop eating. Now, the bothersome aftertaste lingers and I aim to get rid of it with a mint. The mint is one of those crumbly kinds, and after working on it for a bit, I bite straight into it. This leaves little mint bits in my mouth and I want to wash them down with a glass of water. This is a silly example, but the trend holds in much of life. Our actions are very frequently driven by our desire to have or experience things that are pleasant and enjoyable and by our aversion to experiencing things unpleasant or painful. If you keep an eye out, you will likely be shocked at all the (often subtle) instances of this playing out.

However, you will likely find that it is quite difficult to stay aware of these dynamics. What makes it difficult is the automaticity of our reactions to things. We feel pain and we immediately recoil, calling the cause "bad." We feel something pleasing and we immediately move towards it, wanting more. The issue is that we are not seeing the occurrences before us very clearly in these cases and can quickly get caught in the traps of desire and aversion. One can actually see that pain is not something that innately contains "badness." Pain is simply a tactile sensation on which we place our aversion as an overlay. Pain is actually separable from this aversion and can just be felt as the raw sensory data one is taking in, removed from any emotional baggage. That said, this is not easy even with fairly minor pains. Similarly, when we experience something pleasant, we cling to it, and our enjoyment quickly fades to disappointment when we can no longer have the object of our clinging. Again, we are caught up in these extremely fast-acting reactions. As before, one can see the object of desire as distinct from the desire and realize that the desire is another passing feeling. One can let go of this desire and no longer cling to the object. It can be surprising how quickly one lets go after bringing this kind of awareness into the situation. Likewise, with pain, though it is often hard to deal with, it is surprising how much one relaxes after becoming more aware of the situation. The despair we feel from pain is a fear for the future. We are feeling something very unpleasant and wish to no longer feel it. However, we know we will have to, at least into the near future, and this thought frightens us. But we are already enduring the pain in the present moment. We already have the ability to handle the pain and this recognition alone can ease our minds. Then, when looking more closely at the pain, we can separate it from our aversion as described above.

So much of our mental suffering stems from dissatisfaction. We wish we had something or were currently experiencing something. We wish we did not have something or were not currently experiencing something. To have such thoughts, our attention must leave the present. For, how else could we think of something we don't currently have or experience, but want to? How else could we think of no longer having or experiencing something that we currently do? Remaining centered on what is in front of us enables us to let go of these distracted thoughts that do not reflect reality. We can see our immediate surroundings clearly and realize that they are enough. We do not actually need all these other things. If we are in the habit of fixating on what we don't have or aren't experiencing, we will likely continue to fixate even once our current desires are gratified. Instead, we can simply see the automaticity of our desire and aversion and not be swept into the tide. We can watch these emotions appear and disappear without getting wrapped up in them.

Observations of desire and aversion can also strengthen one's compassion and connection to others. One can feel one's own desire for happiness, well-being, and "good" things and one's aversion to sadness, pain, and "bad" things. Everyone feels these emotions (likely many non-human conscious beings do as well). This is a fundamental aspect of our experience and can serve as a common ground with everyone. We can feel a strong connection even with strangers when reflecting on the fact that we are all confronted with happenings in life and often get trapped in our emotional reactions to them. We can see others getting trapped in this way and immediately feel compassion for them since we know all too well what this is like. We can work to be less self-centered by considering the numerous desires and aversions that others are likely facing. So, an awareness of desire and aversion can impact our own well-being and also help us to be better to others.

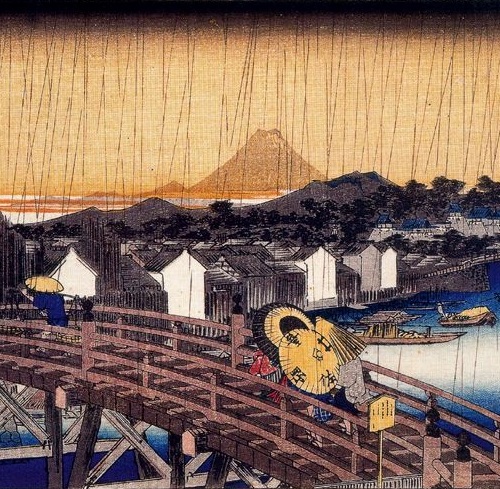

Image: Evening Shower at Nihonbashi Bridge - Hiroshige

Home