August 31, 2020: Conceptual Baggage

The human mind is constantly conceptualizing (or at least mine is). We experience a set of phenomena and immediately encapsulate it in a concept. Emotions exemplify this process. Try this experiment: the next time you feel a strong emotion, see what that emotion actually feels like. How do you know you are, for example, angry? What kind of experiential signature does anger have? In my experience, most emotions are primarily felt as sensations in the chest. Anxiety is often an upward rush through the chest, love is a kind of warm ball centered in the upper torso, etc. The direct experience of emotions is often different from our concepts of them; we don't tend to think of the exact feeling of an upward rush in the chest when we think of anxiety. I believe this pattern widely holds: our concepts about our lives, reality, ourselves, and others rarely match their subject matter in actuality and this has a number of negative consequences.

Take our ideas about plans. COVID-19 has taught me some great lessons on this front. As we start thinking about plans for the future, we begin to make them solid, concrete things in our heads. For example, my past internship this summer was originally going to be in Chicago. After accepting the offer last fall, I began thinking about all the things I'd be able to do in Chicago, all that I wanted to explore, and what my life would be like. These projections into the future had been fleshed out before anything even numerous steps before them had happened. As it turned out, they never would since my internship was made completely virtual due to COVID-19. In the moment of hearing that our plans have been dashed, we experience a feeling of loss. But what, exactly, have we lost? Often, nothing tangible. My plans for Chicago were nothing more than fleeting ideas bouncing around in my head. They represented nothing concrete, pointed to nothing in reality. As we fixate on our ideas about the future, we make something out of nothing. This isn't wholly bad--it's sometimes necessary--but we'd likely save ourselves a lot of heartache and mental toll if we didn't always reinforce this pattern. Again, this is a case of our ideas about reality straying from reality itself. If I had considered what my ideas about Chicago were actually mapping to, I wouldn't have been able to point to anything. I would have recognized that they just represented something that could happen in the future. The mismatch between reality and my ideas about Chicago led to some feelings of loss. However, our concepts have the potential to cause harm beyond the boundaries of our internal lives.

When applied to other people, our conceptualizing can have even more harmful effects. Though many of us mean well and want to avoid placing others in mental boxes by making generalizations about them, our minds often do this automatically and subtly. Many of these mental tendencies have likely proven useful: our minds can save a lot of time and energy by forming a template for a group of things or people and immediately recalling this template when later seeing members of that group. This allows us to not have to relearn everything about that person or thing everytime we see them. This no doubt had survival ramifications for early humans. Being able to quickly identify members of rival or friendly groups could be the difference between life and death. However, in modern society, this habit can have different, harmful effects. In making split-second categorizations of people and things, we can very easily maintain assumptions and ideas about people that are unfair, unflattering, unjust, or simply untrue. It is astonishingly easy to do this--even for the most well-meaning folks. If you ever watch your internal attitudes towards categorizations of people or things, you will quickly see this. As a result, it is helpful to constantly challenge your assumptions--to look past our automatic ideas about people to see what reality is actually like.

Further, when we group people and things in this way, we confine them to simplified, restrictive, and boring versions of their real selves.

Ultimately, this process of "concept cracking" can lead us to see some of the myriad ways we are wrong about reality. It can teach us that--to the dismay of the aspect of our brains that wants to classify, define, explain, and understand everything--reality is much messier, bigger, and more complicated than can often be captured in the neat concepts we dream up. This isn't an all out war on ideas, however. Of course, our ideas are often extremely useful, exciting, and transformative. It is however, a call to constantly stress test our thoughts about "the way things are" to ensure we don't oversimplify and overclassify the world, losing touch with its depth, unpredictability, and incredible complexity.

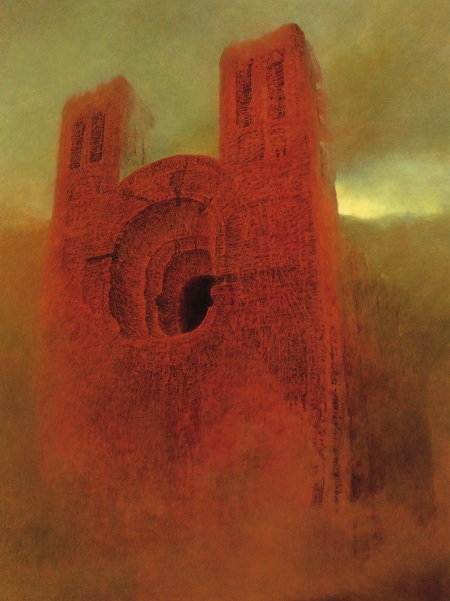

Image: Untitled - Zdzislaw Beksinski

Home